In a defense of One More Day, Joe Quesada described what’s in the core of any successful series.

At the heart of every great character and character universe, there are certain metaphors, iconography and trappings that play a significant part in what makes those characters great. You can deviate from time to time and move away from those things in order to keep the characters and their world’s interesting, but you have to be careful how far you deviate. There is a point where you can go one step too far, to the point where you can’t take it back easily without tearing everything up.

Take the Fantastic Four, for example. What is at the heart of this super hero team? Is it that they’re a team or that they were formed out of a cosmic accident? Is it the high adventure, science fantasy aspect of the book that makes it what it is? Well, all those things are a part of it, but what is really at the heart of the world of the FF is family. Keep the book on point, keep it about family and you’ll be fine. That’s why, Reed and Sue getting married only serves to enhance the FF experience having kids does, as well. On the flip side, Johnny being single works best because it serves as nice counterpoint to a married Sue and Reed.

Now, imagine if we decided to take away the aspect of family from an FF title, what would we have left? Sure, we could still do FF stories. Of course, we’d figure out a way around it, but it wouldn’t be the best that the FF can be. Now, could we remove the element of family for some time in order to make the book interesting, to see what that would be like? Absolutely. But what if we did something that would remove the element of family in a way that couldn’t be reversed properly? Well, then we’ve done a tremendous amount of damage to the title.

Brevoort was criticized for comparing “with great power comes great responsibility” to “criminals are a cowardly and suspicious lot” when few readers consider power and responsibility to be the conceptual engine for the series. It’s worth considering how often DC references Batman’s ability and desire to intimidate criminals, the subject of an interesting write-up about it in Comics Alliance,

I recently read a twelve issue arc from Joe Casey’s Adventures of Superman run. Batman made an appearance for about three pages, and there was an allusion to his love of scaring people. If power and responsibility is supposed to be alluded to as often as fear and symbolism are in the Batman books, it’s still going to be a big part of the Spider-Man books.

That said, it may be too easy for a writer to completely ignore Spider-Man’s origin. One point of Amazing Fantasy #15 that a few writers have sidestepped is that Peter Parker needed that tragedy in order to become a superhero. Otherwise, he would have just used his abilities to enrich himself, which is pretty much the same thing that any normal person would do when presented with an extraordinary opportunity. The tragic twist drove home an important lesson.

Comics historians could argue that a superhero’s origin was typically just window dressing, as a perfunctory explanation of why the guy gets in costume and starts fighting criminals. That arguably changed with Amazing Fantasy #15, when Spider-Man elevated the significance of the superhero’s first appearance. First, his origin was an excellent story in its own right, published as a standalone pilot with a complete beginning, middle and end. The twist hasn’t been topped yet, even with 50+ years of new superhero origins. Several of Stan Lee’s best Spider-Man stories, including the Master Planner saga and Amazing Spider-Man #50, also referenced the lesson of Uncle Ben’s death, adding to the sense that this particular hero’s origin is quite significant.

You didn’t really have that with the Fantastic Four, the Flash, Superman or Green Lantern. Their origins only became important later, as subsequent writers added to the mythologies. Their creators took it for granted that when they gained amazing abilities, they would use those to help mankind.

Viewing power and responsibility as the conceptual engine is rather limiting, because it means that the Peter Parker side of things—which is arguably just as important as the superhero side of things (if not more so)—should be viewed primarily through the same lens. Also, if power & responsibility were the main conceptual engine, Spider-Man could just abandon his life as Peter Parker. Theoretically, he could also come to the conclusion that it’s moral to abandon his responsibilities as Peter Parker because he’ll do greater good as Spider-Man. Even if the last ten years of Aunt May’s life are miserable because of his absence, it’s arguably worth it if he can save one more life.

His greatest impact as Peter Parker may have been preventing Harry Osborn from becoming a successful supervillain. As far as I know, Harry hasn’t killed anyone yet. So Peter could be justified in not paying more attention to Harry Osborn. Or he might figure that if it weren’t for time they devoted to him, Flash & MJ could spend more time with Harry. Even if Peter’s intervention is necessary to save Harry, it objectively might not be worth the time Peter could have spent saving other people.

The flip side of it is that Peter Parker could come to the conclusion that he does more good as a scientist at Horizon Labs then he ever did as Spider-Man. That could be an interesting final story for the Spider-Man comics, but it’s not something that the creative teams should explore quite yet, as publishing demands suggest that the hero can only reach one conclusion to these kinds of dilemmas, since the other option doesn’t allow the series to continue publication.

Quesada had his opinion on what made Spidey unique.

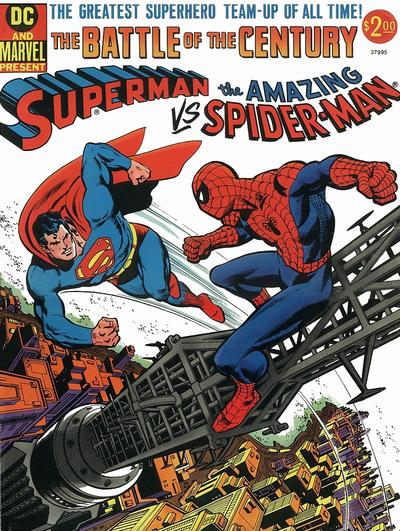

The golden era of Spider Man gave us things we had never seen in a comic before. We had a loveable loser as the hero, a character with some incredible failings, but an amazing amount of heart. “With great power there must also come great responsibility” was his motto, but at the very core of what made Spider Man stories great and, more importantly, different, was the fantastic soap opera and the cast of characters and villains in Peter Parker’s life. Spider Man stories revolutionized the comic book super hero because the stories were about Peter Parker; Spider Man was secondary. This was a big shift from a world in which Superman and Batman were what was important. Clark and Bruce were just facades. And let me add, sometimes Spider Man would lose against the bad guy and sometimes Spider Man wouldn’t make the right decision. These were revolutionary ideas for a super hero comic at the time.

What really made Spidey unique wasn’t so much his powers or his costume, sure those were cool things, but what really made him unique was that it was about the guy inside the costume and the soap opera that was his life. Peter could have had a whole different set of powers and it still would have been a ground breaking comic because in the end, that’s not what made Spider Man stories different. So, with every little bit of the trappings of his life that got chipped away, more and more of the soap opera dwindled.

A talented writer who strips a series to the conceptual engine before plotting the storylines should get consistently good material. One problem I have with viewing power and responsibility as the sole conceptual engine is that it doesn’t seem to be enough, by itself, to support an extended run. The tension between “with great power comes great responsibility” and youth and Peter Parker’s desires is a richer vein.

This is why I think there’s more to the conceptual engine than just power and responsibility, though it is part of it. If it’s just power and responsibility, everything the character does would be viewed through that particular context. However, if the conceptual engine of Spider-Man is the hero trying to balance his responsibilities as a superhero with his responsibilities as a man, it works whether he’s in high school, college or a science lab. It’s muddled when he’s married to a woman with a high-paying job, who also knows his secret identity. And it’s certainly quite different if everyone in the world knows his secret identity. So the changes with One More Day worked well with Spider-Man’s conceptual engine, although it may have affected other aspects of the series.